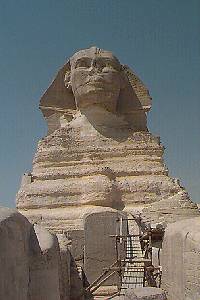

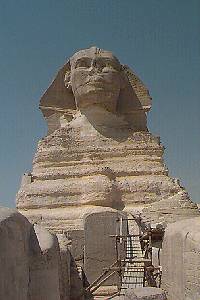

The Sphinx

by P.D. Ouspensky

Photograph ©1998

Guardian

Yellowish-grey sand. Deep blue sky. In the distance the triangle of the Pyramid

of Khephren, and just before me this strange, great face with its gaze directed

into the distance.

I used often to go to Gizeh from Cairo, sit down on the sand before the Sphinx,

look at it and try to understand it, understand the idea of the artists who

created it. And on each and every occasion I experienced the same fear and

terror of annihilation. I was swallowed up in its glance, a glance that spoke

of mysteries beyond our power of comprehension.

The Sphinx lies on the Gizeh plateau, where the great pyramids stand, and

where there are many other monuments, already discovered and still to be

discovered, and a number of tombs of different epochs. The Sphinx lies in

a hollow, above the level of which only its head, neck and part of its back

project.

By whom, when, and why the Sphinx was erected -- of this nothing is known.

Present-day archaeology takes the Sphinx to be prehistoric. [Note: Ouspensky

was writing between 1908-1914.]

This means that even for the most ancient of the ancient Egyptians, those

of the first dynasties six to seven thousand years before the birth of Christ,

the Sphinx was the same riddle as it is for us today.

From the stone tablet, inscribed with drawings and hieroglyphs, found between

the paws of the Sphinx, it was once surmised that the figure represented

the image of the Egyptian god Harmakuti, "The Sun on the Horizon." But it

has long been agreed that this is an altogether unsatisfactory interpretation

and that the inscription probably refers to the occasion of some partial

restoration made comparatively recently.

As a matter of fact, the Sphinx is older than historical Egypt, older than

her gods, older than the pyramids, which, in their turn, are much older than

is thought.

The Sphinx is indisputably one of the most remarkable, if not the most

remarkable, of the world’s works of art. I know nothing that it would

be possible to put side by side with it. It belongs indeed to quite another

art than the art we know. Beings such as ourselves could not create a Sphinx.

Nor can our culture create anything like it. The Sphinx appears unmistakably

to be a relic of another, a very ancient culture, which was possessed of

knowledge far greater than ours.

There is a tradition or theory that the Sphinx is a great, complex hieroglyph,

or a book in stone, which contains the whole totality of ancient knowledge,

and reveals itself to the person who can read this strange cipher which is

embodied in the forms, correlations and measurements of the different parts

of the Sphinx. This is the famous riddle of the Sphinx, which from the most

ancient times so many wise souls have attempted to solve.

Previously, when reading a book about the Sphinx, it had seemed to me that

it would be necessary to approach it with the full equipment of a knowledge

different from ours, with some new form of perception, some special kind

of mathematics, and that without these aids it would be impossible to discover

anything in it.

But when I saw the Sphinx for myself, I felt something in it that I had never

read and never heard of, something that at once place it for me among the

most enigmatic and at the same time fundamental problems of life and the

world.

The face of the Sphinx strikes one with wonder at the first glance. To begin

with, it is quite a modern face. With the exception of the head ornament

there is nothing of "ancient history" about it. For some reason I had feared

that there would be. I had thought that the Sphinx would have a very "alien"

face. But this is not the case. Its face is simple and understandable. It

is only the way that it looks that is strange. The face is a good deal

disfigured. But if you move away a little and look for a long time at the

Sphinx, it is as if a kind of veil falls from its face, the triangles of

the head ornament behind the ears become invisible, and before you there

emerges clearly a complete and undamaged face with eyes which look over and

beyond you into the unknown distance.

I remember sitting on the sand in front of the Sphinx -- on the spot from

which the second pyramid in the distance makes an exact triangle behind the

Sphinx -- and trying to understand, to read its glance. At first I saw only

that the Sphinx looked beyond me into the distance. But soon I began to have

a kind of vague, then a growing, uneasiness. Another moment, and I felt that

the Sphinx was not seeing me, and not only was it not seeing, it could not

see me; and not because I was too small in comparison with the profundity

of wisdom it contained and guarded. Not at all. That would have been natural

and comprehensible. The sense of annihilation and the terror of vanishing

came from feeling myself in some way too transient for the Sphinx to be able

to notice me. I felt that not only did these fleeting moments or hours which

I could pass before it not exist for it, but, that if I could stay under

its gaze from birth to death, the whole of my life would flash by so swiftly

for it that it could not notice me. Its glance was fixed on something else.

It was the glance of a being who thinks in centuries and millennia. I did

not exist and could not exist for it. And I could not answer my own question

-- do I exist for myself? Do I , indeed, exist in any sort of sense, in any

sort of relation? And in this thought, in this feeling, under this strange

glance, there was an icy coldness. We are so accustomed to feel that we are,

that we exist. yet all at once, here, I felt that I did not exist, that there

was no I, that I could not be so much as perceived.

And the Sphinx before me looked into the distance, beyond me, and its face

seemed to reflect something that it saw, something which I could neither

see nor understand.

Eternity! This word flashed into my consciousness and went through me with

a sort of cold shudder. All ideas about time, about things, about life, were

becoming confused. I felt that in these moments, in which I stood before

the Sphinx, it lived through all events and happenings of thousands of years

-- and that on the other hand centuries passed for it like moments. How this

could be I did not understand. But I felt that my consciousness grasped the

shadow of the exalted fantasy or clairvoyance of the artists who had created

the Sphinx. I touched the mystery but could neither define nor formulate

it.

And only later, when all these impressions began to unite with those which

I had formerly known and felt, the fringe of the curtain seemed to move,

and I felt that I was beginning, slowly, slowly, to understand.

[From: A

New Model of the Universe]

![[Image]](pict41.jpg)

![[Image]](pict43.jpg)